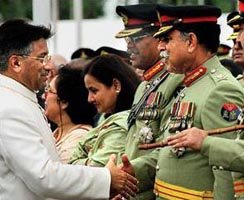

Inside Story about Musharraf-Mahmood Tussle

Hassan Abbas: September 24, 2006

General Pervez Musharraf’s memoir In the Line of Fire is expected to generate a lot of debate and discussion in the days to come. Except some western journalists and Musharraf’s close friends (three ghost writers) hardly anyone has had a chance yet to read the book from cover to cover. The excerpts of the book leaked through Indian media and General Musharraf’s statements to some American media outlets however have already created some controversies. In the United States, controversy is considered a positive thing, so the book is bound to become a bestseller here, but in Pakistan probably the opposite is true.

This article is not a review of the book (as I haven’t got hold of a copy yet), but it endeavors to throw some light on the widely reported Musharraf comment about the Armitage threat conveyed through Lieutenant General Mahmood Ahmed, the then Director General of the ISI. I had done research on this specific question while working on my book “Pakistan’s Drift into Extremism” a couple of years ago, and here are my discoveries and conclusions – some already published and some new. On the eve of the 9/11 terror attacks, in a crucial National Security Council meeting at the White House, Colin Powell, the then U.S. secretary of state, strongly asserted: “We have to make it clear to Pakistan and Afghanistan, this is show time.”

General Mahmood Ahmed, who was on an official visit to the United States as a CIA guest, and Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States, were asked to attend a meeting with senior American officials on September 12, 2001. To be fully prepared, Mahmood called Musharraf to discuss the emerging scenario and take instructions for the important meeting. Musharraf told him to report back immediately after the meeting and gauge how the wind is blowing. On the morning of September 12, the U.S. deputy secretary of state, Richard Armitage, in a “hard-hitting conversation,” told Mahmood that Pakistan has to make a choice—“you are either 100 percent with us or 100 percent against us—–there is no gray area.” In the words of Armitage, Mahmood “was immediately willing to cooperate.” In the afternoon, Mahmood was invited to CIA headquarters at Langley, Virginia, where he told George Tenet, the CIA director, that in his view Mullah Omar, the Taliban chief, was a religious man with humanitarian instincts and not a man of violence! This was a bit difficult for the CIA officials to digest and rightly so as the Taliban’s track record, especially in the realm of human rights, was no secret. General Mahmood was firmly told that Mullah Omar and the Taliban would have to face U.S. military might if Osama bin Laden along with other Al-Qaeda leaders were not handed over without delay. To send the message across clearly, Richard Armitage held a second meeting with Mahmood the same day, informing him that he would soon be handed over specific American demands which are “non-negotiable”, to which Mahmood reiterated that Pakistan would cooperate.

Having gone through the list that was provided to him on September 13, Mahmood declared that he was quite clear on the subject and that “he knew how the President thought, and the President would accept these points.” Mahmood then faxed the document to Musharraf and in a subsequent call conveyed his impressions. Mahmood was of the view that the words used by Armitage about Taliban were infact meant for Pakistan and he didn’t consider it necessary to emphasize this point. Musharraf genuinely believed that such a direct threat was given. While Musharraf had hardly gone through the list of demands, his aide de camp informed him that Colin Powell was on the line. Musharraf liked and respected Powell, and the conversation was not going to be a problem. He told him that he understood and appreciated the U.S. position, but that he would respond to the U.S. demands after having discussed these with his associates. Powell was a bit perplexed at this response and thought it necessary to inform him that General Mahmood had already assured them that these demands would be acceptable to the government of Pakistan. It is not certain if Musharraf bit his lip when he heard this, but he did grit his teeth, and his relationship with Mahmood suffered a crack. Interestingly Mahmood on his return from the US also informed Musharraf about his visit to Pentagon after the tragedy and argued that there were no traces of any commercial plane having hit the Pentagon. He also made a case that in his assessment, the attacks were an inside job! Even some senior generals surrounding Musharraf then were convinced by this line of argument largely based on Mahmood’s “first hand” narrative.

On September 16, 2001, Musharraf sent a delegation to the Taliban with the mission to convince them to hand over Osama bin Laden. It included Lieutenant General Mahmood, and a group of religious figures known to have good relations with Taliban. The mission failed, but more worrisome was the revelation that Mufti Shamzai, instead of conveying the official message, encouraged Mullah Omar to start a jihad against the United States if it attacked Afghanistan. Musharraf came to know of this fact through an ISI official who had accompanied the team and had loyally reported the matter to Musharraf. After this, Mahmood, whose arrogance and presumption had come to grate on Musharraf’s expansive tolerance by now, was offered the ceremonial slot of chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee, because Musharraf was still grateful to him for what he had done for him on the eve of October 12, 1999. Mahmood refused the offer thinking that he was indispensable and a possible successor to Musharraf. But things were changing fast and Musharraf now had the support of most of his corps commanders about his new alignment with the US (except Generals Usmani, Mahmood and Aziz who had advised caution). Gauging the mood of changing circumstances and knowing that Musharraf was about to make some important changes in the military, Mahmood, through a close friend of Musharraf – a retired brigadier based in Islamabad, put in a request to be retained as director general of ISI, even if an officer junior to him is to be promoted as a four star general for the post of CJCSC. This time Musharraf refused and Mahmood had to go home.

This sudden departure of Mahmood led to many rumors and there are dozens of internet sources that hint towards involvement of Mahmood with the 9/11 attacks itself. Ofcourse, all of that is pure rubbish. Mahmood afterwards went into a low profile and started working on his favorite project – a book on the 1965 war. When he finished the work, he sent the manuscript to GHQ for permission to publish. Interestingly the title of the work was “Myth of 1965 victory”. Musharraf, himself looked at the manuscript and noted on the file that Mahmood should re-consider the title – especially use of the word myth in relation to the 1965 war. This was enough of a hint and Mahmood almost shelved the idea of publishing the book for a while. Mahmood had already requested Musharraf for a job and thought that he should not annoy Musharraf on any count. He was right - he got a job soon. And instead Musharraf started working on his book project.

The article was carried by Daily Times on September 25, 2006, which can be accessed by clicking here

For the benefit of Watandost readers, I am posting an excerpt from my book that covers what happened in Pakistan in the aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy. The passages also throw light on Musharraf-Mahmood differences.

Hassan Abbas, Pakistan’s Drift into Extremism: Allah, the Army and America’s War on Terror (M E Sharpe, 2005)

Chapter 10:

9/11 and the War on Terror

Within hours of the deadly September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the U.S. administration concluded that Osama bin Laden and Al-Qaeda operating from Afghanistan were behind the attacks, and that any successful counterstrike would not be possible without the support and assistance of Pakistan. While addressing the American nation after the tragedy, President George W. Bush left no doubt as to the fate of the Taliban regime when he plainly declared that, “We will make no distinction between those who planned these acts and those who harbor them.”1 This led Colin Powell, the U.S. secretary of state, to assert in the National Security Council (NSC) meeting at the White House the same night: “We have to make it clear to Pakistan and Afghanistan, this is show time.”2

Lieutenant General Mahmood Ahmed, Pakistan’s ISI chief, who was on an official visit to the United States as a CIA guest, and Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States, were asked to attend a meeting with senior American officials on September 12, 2001. To be fully prepared, Mahmood called Musharraf to discuss the emerging scenario and take instructions for the important meeting. On the morning of September 12, the U.S. deputy secretary of state, Richard Armitage, in a “hard-hitting conversation,” told Mahmood that Pakistan has to make a choice—“you are either 100 percent with us or 100 percent against us—–there is no gray area.”3 In the words of Armitage, Mahmood “was immediately willing to cooperate.”4 In the afternoon, Mahmood was invited to CIA headquarters at Langley, Virginia, where he told George Tenet, the CIA director, that in his view Mullah Omar, the Taliban chief, was a religious man with humanitarian instincts and not a man of violence!5 This was a bit difficult for the CIA officials to digest and rightly so as the Taliban’s track record, especially in the realm of human rights, was no secret. General Mahmood was told politely but firmly that Mullah Omar and the Taliban would have to face U.S. military might if Osama bin Laden along with other Al-Qaeda leaders were not handed over without delay. To send the message across clearly, Richard Armitage held a second meeting with Mahmood the same day, informing him that he would soon be handed over specific American demands, to which Mahmood reiterated that Pakistan would cooperate.6

Meanwhile, as expected, Musharraf had received his first call from Wendy Chamberlain, the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan. After the pleasantries, she expressed the hope that Pakistan would come on board and extend all its cooperation to the United States in bringing the perpetrators of the terrorist act to justice. He gave her the assurances she sought, but could not restrain himself from enumerating Pakistan’s past experiences of cooperation with America, and the list of broken promises that was the compensation Pakistan often received from such alliances. But Ms. Chamberlain assured him that this time it would be different. For lack of an alternative, he dutifully played the part of a reassured Third World leader.

As per the credible narrative of Bob Woodward, General Mahmood on September 13, 2001, was handed a formal list of the U.S. demands by Mr. Armitage and was asked to convey these to Musharraf and was also duly informed, for the sake of emphasis, that these were “not negotiable.” Colin Powell, Richard Armitage, and the assistant secretary of state, Christina Rocca, had drafted the list in the shape of a “non-paper.” It categorically asked Pakistan to:

1. Stop Al-Qaeda operatives coming from Afghanistan to Pakistan, intercept arms shipments through Pakistan, and end ALL logistical support for Osama bin Laden.

2. Give blanket overflight and landing rights to U.S. aircraft.

3. Give the U.S. access to Pakistani naval and air bases and to the border areas between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

4. Turn over all intelligence and immigration information.

5. Condemn the September 11 attacks and curb all domestic expressions of support for terrorism.

6. Cut off all shipments of fuel to the Taliban, and stop Pakistani volunteers from going into Afghanistan to join the Taliban.

7. Note that, should the evidence strongly implicate Osama bin Laden and the Al-Qaeda network in Afghanistan, and should the Taliban continue to harbor him and his accomplices, Pakistan will break diplomatic relations with the Taliban regime, end support for the Taliban, and assist the U.S. in the aforementioned ways to destroy Osama and his network.7

Having gone through the list, Mahmood declared that he was quite clear on the subject and that “he knew how the President thought, and the President would accept these points.”8 Mahmood then faxed the document to Musharraf. While the latter was going through it and in the process of weighing the pros and cons of each demand, his aide de camp informed him that Colin Powell was on the line. Musharraf liked and respected Powell, and the conversation was not going to be a problem. He told him that he understood and appreciated the U.S. position, but that he would respond to the U.S. demands after having discussed these with his associates.9 Powell was far too polite to remind him that he in fact was the government, but did inform him that his general in Washington had already assured them that these demands would be acceptable to the government of Pakistan. It is not certain if Musharraf bit his lip when he heard this, but he did grit his teeth, and his relationship with Mahmood suffered a crack. Musharraf was in no doubt that, in the circumstances, he would have accepted every American demand, but only after putting up the right appearances. Mahmood’s presumption had denied him the act and national prestige had suffered a blow, though the bruise must have shown more clearly on his personal ego, which has as large a compass, as it is tender.

Musharraf’s response to Powell was in line with his earlier statement on the eve of the 9/11 tragedy—he had condemned it as the “most brutal and horrible act of terror” and in his message to President Bush had said that the world must unite to fight against terrorism in all its forms and root out this modern-day evil.10 Later, discussions with Wendy Chamberlain and a telephone conversation with General Mahmood in the United States on the issue had helped him gauge the direction in which the wind was blowing. On the eve of September 12 he had already discussed the issue in Pakistan’s National Security Council and made up his mind. But he was not expecting an “either you are with us or against us” proposition, with a specific seven-point demand list and a very short deadline to respond. To reply, he intended to take the army corps commanders in confidence, but courtesy of Mahmood, he had to immediately give the U.S. administration all the assurances they needed from Pakistan, though there was to be no public declaration of the same because Musharraf needed an ex post facto formalization of the same after meeting with his corps commanders

Corps commanders, on the other hand, were unaware of this development when they all met in a nuclear bunker near Islamabad on September 14, 2001, believing that they could talk without the risk of U.S. surveillance in a highly secured location. Nine corps commanders and a dozen other senior staff officers at the army’s General Headquarters (GHQ) were in attendance, including the chiefs of the ISI and MI. Musharraf gave out a cogent exposition of why Pakistan had to stand with America. He told them that Pakistan faced a stark choice—it could either join the U.S. coalition that was supported by the United Nations Security Council, or expect to be declared a terrorist state, leading to economic sanctions. Most of his commanders nodded in sage agreement, but General Mahmood sat in sullen silence; Lieutenant General Aziz registered his polite disagreement; General Mushtaq was entirely consistent and honorable in dissent; and the unfortunate Lieutenant General Jamshed Gulzar seemed to have lost his sanity and discovered his nonexistent heroism to join the dissenters. But it was General Khalid Maqbool who really sparkled, giving a glittering performance of unctuous courtiership. In the process he won the heart of Musharraf by pleading his infallibility. And Lieutenant General Usmani, the number two man in the army, a self-confessed “soldier of god,” registered his impolite disagreement. Usmani had started out as a moderate and an open-minded officer, but later in his career he found the intolerant fringe of Islam, where he saw his own piety in discovering the imperfections in others. By the time he became deputy chief of army staff, he had become reclusive, shutting himself in his house and walking about in a Saudi jubba (gown) topped by a green turban. All this was widely known when Musharraf promoted him.

General Usmani’s argument was that ditching the long-standing Pakistan policy of supporting the Taliban without any specific American incentive in return should be avoided.11 On the contrary, Musharraf was of the view that Pakistan should be supportive of the United States as a matter of principle, and any hint of economic incentives would be inappropriate at a time when the United States was in a “shock and anger” mood.12 Lieutenant General Aziz, on the other hand, was of the view that there was a possibility of a domestic backlash if Afghanistan were attacked, to which Musharraf agreed, but he insisted that in case of any delay in agreeing to the U.S. terms, India would benefit by currying favor with the United States. This was a sufficient argument for the Pakistani military commanders to agree with Musharraf’s opinion, though it took them six hours to reach this “consensus.”

The next day, on September 15, Musharraf conveyed General Aziz’s concerns about a possible domestic fallout to Wendy Chamberlain without naming him, explaining that in such an eventuality Pakistan would expect the United States to understand such pressures and continue to support him.13 The message was duly conveyed to senior officials in the U.S. administration.

The point that had helped Musharraf clinch the argument during the corps commanders’ meeting a day earlier, in reference to India, was in fact substantial. Of course, Musharraf and his corps commanders were unaware that hardly a few hours before their meeting had commenced, the leading Indian intelligence service, named the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), had convinced the CIA that “Pakistani jihadists” were planning an “imminent attack on the White House,” and as a precautionary measure the U.S. Secret Service had even made arrangements to evacuate President Bush from the White House.14 President Bush was understandably exhausted by the hectic schedule and attendant pressures, hence to the surprise of everyone he refused to leave the White House until shown the exact information. U.S. Secret Service director Brian Stafford told him that he was in immediate danger and that the report was credible, as Indian intelligence was well wired into Pakistan, but the president was unmoved. Still, the threat was considered so serious that Vice President Dick Cheney was shifted to a safe location and nonessential staff at the White House were allowed to go home early. This explains the credibility of Indian intelligence in the eyes of the CIA, but most likely its privilege and trust was misused in this case. Arguably, it was an effort on the part of India to push the U.S. administration to include Pakistan on the hit list. Without a doubt, religious extremists are narrow-minded bigots and violence indeed is their bread and butter, but to make a case that any of the domestic Pakistani groups (e.g., Lashkar-i-Taiba and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi) were capable of launching a terrorist attack on the White House was an exaggerated assessment. The report also inferred that Pakistani intelligence possibly was sponsoring this attack, which was not possible. For the sake of argument, even if the Pakistani jihadi groups were capable of orchestrating such a strike, Indian intentions behind providing this “timely” intelligence assessment were less than noble.

On September 16, 2001, Musharraf sent a delegation to the Taliban with the mission to convince them to hand over Osama bin Laden. It included Lieutenant General Mahmood, the ISI chief, and Mufti Nizamuddin Shamzai, head of the famous Deobandi Madrasa in Binori town, Karachi. It is the same Madrasa where Osama bin Laden first met Mullah Omar, the leader of the Taliban, a few years ago. The mission failed, which was expected, but more worrisome was the revelation that Mufti Shamzai, instead of conveying the official message, encouraged Mullah Omar to start a jihad against the United States if it attacked Afghanistan.15 After this, Mahmood, whose arrogance and presumption had come to grate on Musharraf’s expansive tolerance by now, was offered the ceremonial slot of chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee.16 He refused.

However, Musharraf was under immense pressure, both domestically and from the United States on how to proceed vis-à-vis U.S. demands and expectations. While talking to a selected gathering of retired generals, seasoned diplomats, and politicians, on September 18, Musharraf argued that the decision to extend “unstinting support” to the United States was taken under tremendous pressure and in the face of fear, that in case of refusal, a direct military action by a coalition of the United States, India, and Israel against Pakistan was a real possibility. When confronted by the audience that he still should have consulted a cross-section of society before taking any decision, he mentioned the short deadline he was given for a response.17 It was easy for Musharraf to have a dialogue with this group, but leaders of Jamaat-i-Islami and Jamiat-i-Ulema-i-Islam (both Sami and Fazl groups) were not ready to listen to Musharraf’s justifications. They asked for a review of government policy and insisted that Musharraf demand from the United States a credible evidence of bin Laden’s involvement in the 9/11 attacks. This was what the Taliban also asked for a day earlier. On September 18, when a journalist posed this question to the U.S. secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld, his reply was that sharing intelligence with other countries posed a dilemma as that could lead to a drying up of sources of information.18 But Musharraf was finally shown some evidence on October 3, 2001. A day later the Pakistan Foreign Office declared that the “material provides sufficient basis for [bin Laden’s] indictment in a court of law.”19 Musharraf should have been allowed to share the information with the people of Pakistan.

Any how, Musharraf knew that war was coming to Afghanistan. On October 7, 2001, the U.S. attack on Afghanistan commenced, and what was left of the country was bombed to smithereens. The many dead did not receive the dignity of even a decent count. The sheer magnitude of the effort stunned the people, and the Pakistani clerics were unnerved for the first time since their steady rise in influence and power, which helped Musharraf consolidate his position. Pakistan had taken a historical U-turn in its policy toward the Taliban by fully supporting the U.S. military campaign. On the domestic scene, Musharraf started to announce measures against the hard-line religious groups and limit the license of the mullahs. Most Pakistanis heaved a sigh of relief—for those oppressed by all and sundry, suppression of the mullahs was to be one oppression less.

This change in policy needed a change of faces as well. Gauging the mood, Mahmood, through a close friend of Musharraf, put in a request to be retained as director general of ISI.20 Musharraf refused and Mahmood had to go home. General Aziz retained the esteem and affection of his boss to fill the office so recently refused by Mahmood, and General Usmani packed his bags and vanished. Shortly thereafter Generals Mushtaq and Gulzar lost their commands and were sidelined, and Khalid Maqbool, was made governor of the largest and most populous province in the country. With General Ghulam Ahmed already having passed away, and General Amjad not being a part of Musharraf’s inner core, there was no one left in the fighting army with courage enough to register a disagreement with their chief. Ironically, Musharraf mistakenly took this as an omen of his rising popularity in the army.

NOTES

1. Text of President Bush’s speech on September 11, 2001; last accessed May 15, 2003, at http://www.cnn.com/2001/US/09/11/bush.speech.text/.

2. Bob Woodward, Bush at War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), p. 32.

3. Owen Bennett Jones, Pakistan: Eye of the Storm (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002), p. 2.

4. Interview: Richard Armitage, “Campaign Against Terror,” PBS (Frontline), April 19, 2002; last accessed June 2, 2003, at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/campaign/

interviews/armitage.html.

5. Woodward, Bush at War, p. 47.

6. Jones, Pakistan: Eye of the Storm, p. 2.

7. Woodward, Bush at War, pp. 58–59.

8. Interview: Richard Armitage, “Campaign Against Terror,” PBS (Frontline), April 19, 2002.

9. Interview with a staff officer of General Pervez Musharraf, June 2002.

10. “Musharraf Condemns Attack,” Dawn, September 12, 2001.

11. Jones, Pakistan: Eye of the Storm, p. 3.

12. Interview: President Pervez Musharraf, Campaign Against Terror, PBS (Frontline), May 14, 2002; last accessed June 6, 2003, at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/campaign/

interviews/musharraf.html.

13. Ibid.

14. The episode is narrated in Woodward, Bush at War, pp. 55–57.

15. S. Hussain, “Clerics Violated Official Brief During Visit to Afghanistan,” Friday Times, October 7, 2001.

16. Interview with a senior staff officer at GHQ.

17. “Pakistan Baking U.S. Under Pressure: CE Briefs Think Tanks,” Dawn, September 19, 2001.

18. Department of Defense News Briefing, September 18, 2001. For the transcript, see www.defenselink.mil.

19. Transcript of the press conference addressed by the Foreign Office Spokesman, October 4, 1001, at www.pak.gov.pk.

20. Ibid.

No comments:

Post a Comment